William George “Bill” Fowler was born in Calgary, Alberta, the youngest child of Thomas and Margaret Ann Fowler. He grew up in Edson, Alberta where his father, who had emigrated from Scotland, operated a trucking business.

When the war began, the 9th Army Troops Company, Royal Canadian Engineers, was mobilized in Edmonton, Alberta and started recruiting throughout the central part of the province including the town of Edson where Bill enlisted on 20 Sep 1939. He was very soon living in a group of quickly thrown-together temporary huts around the Prince of Wales Armoury in Edmonton where the company was headquartered.

For the next seven months, the company trained to the extent possible, given shortages of equipment, staff and training areas. Initially, training activities focused on basic soldiering skills – drill, small arms, first aid, map reading, physical fitness, as well as building and improving their accommodations. Skilled soldiers took trades tests at the Technical High School in the building trades and at government agencies for regulated trades such as stationary engineering. Junior leaders were selected and officers were sent on advanced training courses. Medical examinations, dental and inoculation parades were also time-consuming in the early days.

As the 1st Canadian Division had to be fully kitted before being shipped to the United Kingdom, getting proper uniforms was a challenge and in November, the company handed over all their personal webbing to 1st Division units preparing to deploy to the United Kingdom. Only in January 1940 did enough battle dress arrive for issuing to all personnel in the Company.

In January, elements of the 1st Canadian Division raised in Edmonton started entraining for the east coast, including William’s older brother Walter who would serve in the field artillery during the Italian and Northwest European campaigns. The 9th Army Troops Company often provided guards and security as troops boarded trains. Through the winter, played on the Garrison hockey team which did well in many competitions around Alberta. In March, Bill passed the tests necessary to qualify for promotion to corporal.

In early April 1940, the company learned it would be soon disbanded and troops would be sent to the 1st Pioneer Battalion, RCE being formed in Toronto. Troops were recalled from furlough and embarkation leave was authorized for most men. This was followed by a flurry of activity as the company rushed a general clean-up, returned garrison stores, and packed and loaded. They left Edmonton on 22 April and arrived three days later in Toronto. Most troops were used to bring ‘A’ Company and Battalion HQ Company up to strength.

The 1st Pioneer Battalion was housed in barracks at the Canadian National Exposition and the University Avenue Drill Hall, under command of Lieutenant Colonel James Melville, MC, ED . Initial training was constrained learning and practising basic sapper skills including knots, lashings, small arms training, and getting kitted out. William was promoted to Lance Corporal on 31 May 40, but soon reverted to the rank of Sapper due to a disciplinary matter.

The 1st Pioneer Battalion left Toronto on 7 June 1940 and arrived in Liverpool from Halifax on 20 June. While most of the battalion was sent to Aldershot in Hampshire and was to be employed in construction tasks over the next year, Bill was among those selected to go directly to the Canadian Engineer Reinforcement Unit (CERU) for more sapper training. In August 1941, he was posted to the 2nd Field Park Company which had been in the UK since December 1939 and was now stationed in Alderstead Heath near Aldershot in Surrey. They moved to Billingshurst in Sussex in October.

A Field Park Company provided the workshop and stores elements for the division’s three Field Companies. Nearly half the sappers were tradesmen, mechanics or drivers. Besides a normal complement of basic military vehicles to meet the company’s own administrative needs including carrying engineer stores, the company held a significant allocation of engineer equipment including dozers, compressors and compressor tools, trailers, cranes and tractors. Engineer stores including picks, shovels, assault boats, reconnaissance boats, two small box girder bridge sets, explosives and anti-tank mines were also held and loaded on trucks. As well, there was an array of infantry weapons including rifles, Bren guns, Sten guns, light anti-aircraft guns and PIAT anti-tank weapons. The total strength was about 160 all ranks. As a motorcyclist, Bill was likely assigned to the Company Headquarters as a messenger.

For most of the time Bill served in the 2nd Field Park Company, activities were aimed at supporting the training of the three field companies in the division. They provided equipment and transport as needed, all the while maintaining their own vehicles and tools. Tradesmen were involved in construction and defence works projects in and around the various Canadian camps in the area. Many soldiers had the opinion that life in a field park company was better than in a normal field company. Not a month went by when the officers were not conducting trades tests for potential transfers. Company officers also made personal visits to the CERU to interview potential members.

In June 1942, Bill was posted to HQ 1st Canadian Divisional Engineers, RCE located at the West Sussex Golf Club, near Pulborough. Having stated his trade as being a truck driver and motorcyclist on enrollment, it was natural that Bill received the trade qualification of Driver in August 1942. He was again appointed Lance Corporal for a short time, but after 14 days in detention in October, he reverted to his permanent rank of Sapper.

The HQ was small but a very busy organization. They oversaw all aspects of engineer support to the division. Lieutenant Colonel Geoff Walsh had the appointment as Commander Royal Engineers (CRE) and commanded all aspects of RCE support in the division – three field companies, a field park company and the divisional engineer HQ. In addition, he acted as the engineer adviser to the divisional commander. Sapper Fowler was the CRE’s driver and was kept very busy as Colonel Walsh did his rounds of the companies in garrison and on exercise. The number of officers and men on establishment was six and 31 respectively, but at any one time, there could be up to a dozen more officers and men attached for special assignments.

In December 1942, the focus of the 1st Division’s training started to take on a different flavour. Up until that time, their prime focus had been on the defence of Britain against a German invasion. It was now obvious that the Allies were preparing to take the fight to the enemy. Advance elements of the HQ staff, as well as the three field companies and field park company, visited the Combined Operations Training Centre near Inveraray in Scotland to prepare for exercises that would start in January. The next six months included amphibious operations, mountain warfare and individual fighting skills.

By June 1943, the 1st Division’s Engineers, and their HQ, were in Scotland taking part in what would be their final amphibious exercise when they learned they would soon go into action. The HQ worked out loading tables for men, equipment and supplies that would be needed to support an assault. Troops began exchanging their woolen battledress for tropical clothing and trained to waterproof their vehicles. Every soldier was on edge with tensions rising and rumours spreading about where and when they would see action. Would it be Greece? Crete? Sicily? As training wrapped up, they were issued tropical clothing and loaded on ships.

The total strength of Canadian units that would embark on Operation "Husky" was over 26,000 officers and men with tanks, guns and enough supplies to sustain three weeks of fighting. The main invasion force would sail in two convoys with the combat units divided between the "Fast Assault Convoy" carrying the actual landing force and the "Slow Assault Convoy" carrying the follow-up troops. The Slow Assault Convoy would sail first and meet the Fast Assault Convoy off Malta on D minus 1. The ‘Slow Assault Convoy’ left in two groups on 19 and 24 June 1943. Taking different sea routes for reasons and security and safety, they would meet near Algiers. It carried troops, equipment and supplies not needed for the initial assault.

The HQ War Diary records that on 1 June, Sapper Bill Fowler along with two others left the HQ with the CRE’s jeep and signals van and drove vehicles to Dumfries, Scotland. As part of the Slow Assault Convoy, they were loaded on the MV Devis along with detachments from units of 3 CIB and Division HQ, including HQ Divisional Engineers. Its main cargo included mechanical transport, heavy weapons and stores for the follow-up wave. It carried 22 of the Division Headquarters' 26 motor transport vehicles, half of the division's 17-pounder antitank guns, some field artillery pieces, important signal equipment and engineer stores. Soldiers on board included detachments from the Carleton and York Regiment, the Royal 22e Regiment, the 1st Anti-Tank Regiment and the 4th Field Company.

Once at sea, the troops focused on physical training, washing, eating, fatigues, games and lectures emphasizing first aid, sanitation and the treatment of prisoners of war and civilians. It was not until 1 July 1943, as they neared the Strait of Gibraltar, the men aboard the ships learned they were part of Montgomery’s 8th Army and were headed to Sicily. With the announcement, a sealed bag containing detailed orders, maps, aerial photos, operations orders and intelligence pamphlets was opened on each ship along with a large-scale relief map and officers and men developed a solid vision of the topography upon which they would carry out their mission. This was in strict compliance with General Montgomery’s direction that every soldier would go ashore physically fit and knowing what was required of him.

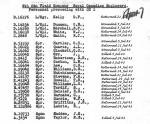

For the fast assault convoy, the passage was easy, but not so much for the slow convoy. After passing through the Strait of Gibraltar, the slow convoy was attacked by submarines and had three ships torpedoed and sunk. On the night of 4 / 5 July, the MV St. Essylt and the MV City of Venice were torpedoed. The St. Essylt was abandoned in flames and the City of Venice sank while being towed to Algiers. Six Canadian soldiers were lost along with a significant amount of equipment and supplies. The next afternoon, MV Devis was also hit, just aft of amidships and just below the soldiers’ mess deck. On a normal afternoon, most troops would be above deck actively training or resting. Unfortunately, on that day, at that time, many of the troops on board were on the mess deck receiving their monthly dose of anti-malarial medicines. The explosion killed anyone on the mess deck and set fire to the ammunition stores separating the front from the back of the ship. Other men were trapped below decks when the fire cut off their escape route. Amazingly, despite the fire, there was little panic and 257 men were able to abandon ship only when the order was given.

The ship sank 20 minutes after being hit taking 52 Canadian soldiers and a considerable amount of equipment, including the CRE’s jeep and van, with it. Bill Fowler was on the mess deck and was one of five sappers killed in the attack and five more wounded. Fourteen of the rescued sappers were able to turn to their unit in Italy later that month.

Sapper William George Fowler is memorialized at Cassino. He was 23 when he died.